Living Peace: Letters of Wars and Peace

20. 12. 2024 | Politics

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

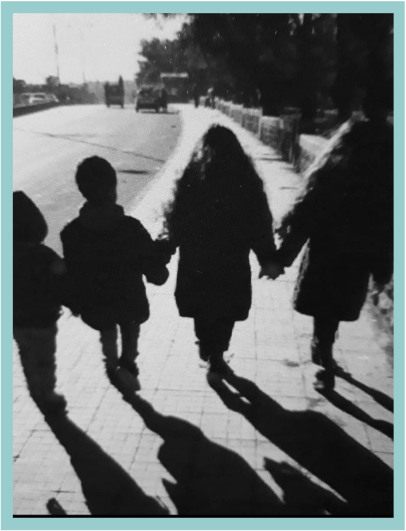

We want to expand on the Thinking Peace cycle and add new dimensions to imagining peace. With the help of amazing individuals worldwide, we are beginning a new series of public letters written by people whose lives were interrupted by war or who found themselves in a recent armed conflict. We have titled this series of letters as Living Peace to emphasize how important peace is and that people often only realize this importance when facing the brutality of war. We want to illustrate how people from Palestine, Ukraine, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Congo, Yemen and elsewhere think publicly about peace. How do the inhabitants of these regions face wars and military conflicts? What lessons can we learn from their intimate experiences and existential fears?

While opinions of world leaders who justify or even defend wars, dominate today’s media spheres, we want to amplify the voices that defend peace, reject violence and recognize equal rights for all. Having experienced war, they understand why it is essential to live in peace.

The first letter we are publishing was written by Aber from Syria: “The idea of killing is mad, harsh, and dark; it clashes with human nature, which leans toward goodness.” The letter was written before the fall of Assad’s regime.

Letter by Aber from Syria

Is humanity greater than war, or is war greater than humanity? Should a person die for the cause, or live to achieve the goals of the cause? Why must a person die to achieve the goals of a cause?

Is humanity greater than war, or is war greater than humanity? Should a person die for the cause, or live to achieve the goals of the cause? Why must a person die to achieve the goals of a cause?

In the beginning, was it war, or was it peace? War and peace, or peace and war. The idea of killing, of crime, as the holy books told us, began with the story of the first murder in human history: Cain, the son of Adam, killed his brother Abel. Abel lay lifeless, his blood soaking the earth. Cain’s sorrow was great, his regret painful, but his grief and remorse could not turn back time or prevent the crime from happening. And the holy books tell us that Cain didn’t know how to deal with his brother’s body after his death until he saw a crow and learned from it how to bury the body in the ground.

The idea of killing is mad, harsh, and dark; it clashes with human nature, which leans toward goodness. The concept of killing and the concept of war are always ugly, always bring destruction, death, suffering, loss, and do not align with a woman’s nurturing nature or her soft femininity. A woman represents beauty, life, fertility, safety, stability, and giving. Here, we can understand the extent of a woman’s suffering during war.

Our human history has a long record of wars; from the beginning of creation, there have been conflicts and wars. During the First World War from 1914 to 1918, the immediate cause was the assassination of the Austrian crown prince and his wife by a student from Serbia on June 28, 1914. After a period of relative calm, the Second World War began, spanning from 1939 to 1945.

I mention the First and Second World Wars because, for me at least, they contain the same cruelty and violence as what has been happening in my country, Syria, since 2011 to this day. War is war. Killing is killing. Blood is blood. Whether it’s a regional, international, or civil war, a woman’s suffering in these conflicts is the same, unfortunately.

What has happened and continues to happen in Syria has been documented in terrifying numbers by both international and local observatories—Arab and Western—revealing horrific rates of rape, forced disappearances, and death under torture. Syrian women have suffered greatly from this, losing the most basic necessities of life. One well-known story in Syrian circles tells of a prominent Syrian opposition politician who was in prison. His jailer challenged him to tell a story to a child in the prison. The child was around five years old, his face pale and yellow from a lack of sunlight. The politician tried to engage the child’s imagination, starting with, “Once upon a time, there was a bird…” But the child interrupted him, asking, “What is a bird?” The politician continued, mentioning a tree, but again, the child interrupted, asking, “What is a tree?”

It dawned on the politician that the child had never been outside the prison walls, knowing nothing but confinement and his mother, who had given birth to him in prison from the seed of her jailer. His mother was only 22 years old when she was detained and raped in prison.

This story encapsulates what has happened in Syria. Syria—Damascus, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, with an uninterrupted history of nearly eleven thousand years. Syria, the East, Syria of religious tolerance, Syria of the Eastern Church, Syria of the Umayyad Mosque. Syria, with its civilization, history, culture, poetry, and literature. Syria of Bosra al-Sham and the Great Umayyad Mosque, where both Muslims and Christians once worshipped since the conquest of the Levant. My maternal grandmother was Christian and used to tell us many stories and read in both Arabic and French. I still remember her joy when Pope John Paul II visited Syria, becoming the first pope in history to enter a mosque when he stepped into the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, tracing the footsteps of Saint Paul.

How could the world watch Syria be destroyed, distorted, and violated without raising a voice? Even when the world did speak up, it was in a way that was ineffective. East and West remained silent.

The East, which gave us the Arab philosopher Averroes, celebrated by the West; many considered his works to be one of the intellectual foundations of its revival. And the West gave the world the philosopher Immanuel Kant, to whom we all owe an apology for not appreciating or applying his immense contributions. Forgive us, Kant, for not applying your grand vision of peace when you said:

- The preliminary treaty is the prior intention and desire to achieve peace, so that the project of peace does not turn into a temporary truce, essentially a rest before submitting anew.

2. No state, however powerful, should dominate another.

3. One condition for lasting peace is the abolition of armies. (Here, I sincerely apologize, Kant).

4. No state should borrow funds to finance foreign conflicts.

5. No state should interfere in the governance or system of another; Russia and Iran’s actions in Syria are examples.

6. In times of war, no state should engage in actions against another that would make reconciliation untrustworthy after a return to peace.

Here, we realize the difficulty of achieving this vision, though it’s compelling, because governments resist committing to anything that conflicts with their interests. But today, civil society institutions attempt to fill this role, proposing ideas for global discussion and pressuring governments to maintain a global balance in line with international rights.

War, justice, peace—fertile narratives and intertwined events provide a rich source for literature, especially war, which has an unparalleled ability to evoke storytelling and enrich a writer’s imagination. This brings to mind one of the most famous novels on the subject of war: War and Peace by Russian writer Tolstoy. Through reading this novel, we gained a deeper understanding of Russian society’s emotional experience during the Napoleonic invasion. Poetry and writing are often the last resort for noble surrender.

War, justice, peace—fertile narratives and intertwined events provide a rich source for literature, especially war, which has an unparalleled ability to evoke storytelling and enrich a writer’s imagination. This brings to mind one of the most famous novels on the subject of war: War and Peace by Russian writer Tolstoy. Through reading this novel, we gained a deeper understanding of Russian society’s emotional experience during the Napoleonic invasion. Poetry and writing are often the last resort for noble surrender.

The apparent goal of all wars and revolutions may seem to be freedom and liberation from dictatorial rule, taking into account social, economic, and behavioral conditions in society. Humanity didn’t realize the harshness of wars until they were already in them. After the end of the First World War, new nations emerged, different from those known before its outbreak. The same was true after the Second World War, which put the entire world between the jaws of two powers: the hammer of communism and the whip of gentle capitalism.

But after the harsh experiences of the two world wars, modern humans finally realized they were merely pawns and that freedom was nothing more than a myth spun in ways that served the ambitions of power and control.

I lived in a prison, or perhaps more accurately, a large prison. The conditions of my confinement were acceptable at the time. I didn’t think of improving them, or maybe I didn’t consider it a prison in the sense understood by those familiar with the rhetoric of power.

The hardest thing a prisoner could wish for is freedom after realizing they are in prison. The price of freedom is the destruction of the prison walls. Freedom shines from afar, and the prisoner then sees the value of light in the darkness of the cell.

Europe glimmered like a bride’s bracelet on a horse, waiting for a prince to sweep her away. When I arrived in Europe after a long journey filled with fear—for my life, for the lives of my family and young children, and for what remained of me after escaping prison, a place I had come to know well—I knew the street where I lived, the names of my neighbours, and if I cried, I would hear the consolation of the neighbours, as if they were saying, “We are free prisoners; outside, they envy us for the comfort we have. Here, we don’t think of anyone, and no one thinks of us.”

In Europe, I didn’t recognize walls—not of prisons, rooms, or hotels. Dark prisons are prisons without walls, prisons without guards, prisons without visiting hours, without uniforms for prisoners.

All I longed for was to have a room, a bed, and a mailbox for letters—letters from friends on birthdays, letters from my sick mother in Syria, a condolence message after my father’s death.

Here, I became a vast prison, holding all my memories and recollections, dreaming of a home, dreaming of imagining freedom, dreaming of the warmth of that prison there, and wishing I hadn’t left that prison.

But can a person ever be freed from their memories? As long as I see myself as human, I will remain a prisoner of myself, wherever I am.

Letter by Aber in Arabic and Slovenian

Thinking Peace website