Living Peace 6: Letters of Wars and Peace

30. 1. 2025 | Politics

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

We want to expand on the Thinking Peace cycle and add new dimensions to imagining peace. With the help of amazing individuals worldwide, we are beginning a new series of public letters written by people whose lives were interrupted by war or who found themselves in a recent armed conflict. We have titled this series of letters as Living Peace to emphasize how important peace is and that people often only realize this importance when facing the brutality of war. We want to illustrate how people from Palestine, Ukraine, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Congo, Yemen and elsewhere think publicly about peace. How do the inhabitants of these regions face wars and military conflicts? What lessons can we learn from their intimate experiences and existential fears?

While opinions of world leaders who justify or even defend wars, dominate today’s media spheres, we want to amplify the voices that defend peace, reject violence and recognize equal rights for all. Having experienced war, they understand why it is essential to live in peace.

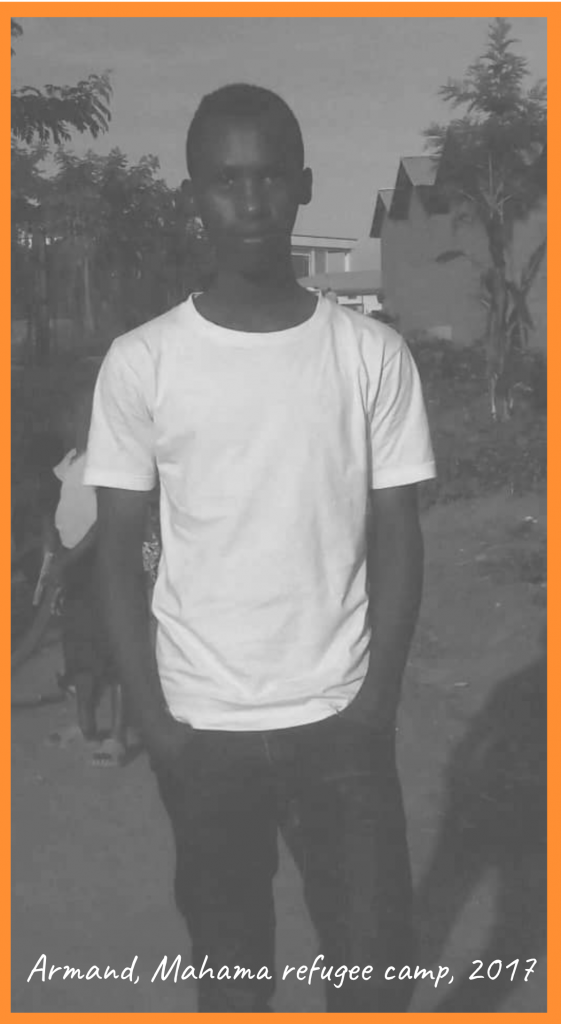

The sixth letter we are publishing was written by Armand from Burundi:

One of the biggest lessons I have learned is that peace doesn’t happen on its own. It requires hard work, commitment, and cooperation. Many conflicts arise because people feel like they are not heard, marginalized, or oppressed. To create lasting peace, we need systems that make sure everyone’s voice is heard, and that justice is applied fairly.

Reconciliation is also a very important part of this process. In Rwanda, the long and painful process of reconciliation after the 1994 genocide has shown us that peace is possible, even after the worst tragedies. But it requires forgiveness, honest dialogue, and a commitment to healing the wounds of the past. It’s not an easy process, but peace must take root.

LETTER BY ARMAND, BURUNDI:

Dear friends of peace,

Dear friends of peace,

My name is Armand Dushime, and I want to share my story as a refugee and how education helped me heal. In 2015, my family and I had to flee from our home and seek safety in Rwanda after my father, a retired soldier, was falsely accused of hiding weapons and training rebels. These accusations were not true, but we had to run for our lives. I was just a secondary school student at the time, and I could never imagine that my life would change so suddenly.

We lost everything—our home, our community, and the security we had always known. Becoming a refugee wasn’t just about losing material things like our house. We have also lost our sense of identity and belonging. I felt emotionally lost for a long time, and the pain was overwhelming.

Life in the refugee camp

Life in the refugee camp

Life in the refugee camp was very hard. The conditions were harsh, and resources were limited. Many young people like myself found themselves struggling to survive. Some turned to illegal activities to cope with their situation, and this has also left a deep scar on me.

We also faced challenges when it came to resources. When we arrived at the camp, we received firewood every month as part of humanitarian aid, but it wasn’t enough to last us the entire month. To survive, many of us who couldn’t afford charcoal would secretly cut down trees from nearby farms. The Rwandan farm owners sometimes caught us, and they would either beat us or insult us. This went on for four years, until 2019, when the UNHCR provided the camp with gas stoves.

Receiving education in the camp was another big challenge. The classrooms were overcrowded, with too many students per teacher, and there weren’t enough learning materials for us to study properly. These conditions were unbeneficial for learning and made it hard for pupils to focus or hope for a better future.

I was full of anger. I was angry at the people who had accused my father and caused all this suffering for my family. I was also angry at the injustices that we were experiencing as refugees. I felt stuck in a cycle of hatred and revenge, and I didn’t know how to move forward.

The emotional impact of conflict

Conflict doesn’t just destroy homes—it destroys lives. My family, like many others, lived in fear and uncertainty. The fear of what might happen next, the fear of losing more of our loved ones, and the fear that we might never find safety again hurt us every day. The trauma of leaving our home stayed with us, and it deeply affected our emotional well-being.

Despite these difficult situations, many of us still held onto hope. We tried to find ways to rebuild our lives, whether it was through education, through work where it was available, or simply supporting each other in small ways.

Education and the path to healing

Education and the path to healing

The turning point for me came in 2022 when I started attending Peace and Conflict Studies at the Protestant University of Rwanda (PUR). This education was life-changing for me. I learned that conflict is often driven by complicated factors like politics, economics, and social pressures. Through my studies, I also began to understand that many of the people who commit violent acts are themselves victims of different pressures.

At PUR, I met people from many different backgrounds. Many of them had experienced suffering far worse than mine, and hearing their stories helped me to understand that holding onto my anger was only hurting me. I learned about the power of forgiveness and reconciliation. Education taught me how important it is to find non-violent solutions to conflict.

Education was my way to heal. It helped me let go of the pain and anger that I had carried for so long. It has also opened my eyes to the possibility of a better future—one where peace is not just the absence of war but the presence of justice, fairness, and understanding.

The lesson learned about peace

One of the biggest lessons I have learned is that peace doesn’t happen on its own. It requires hard work, commitment, and cooperation. Many conflicts arise because people feel like they are not heard, marginalized, or oppressed. To create lasting peace, we need systems that make sure everyone’s voice is heard, and that justice is applied fairly.

Reconciliation is also a very important part of this process. In Rwanda, the long and painful process of reconciliation after the 1994 genocide has shown us that peace is possible, even after the worst tragedies. But it requires forgiveness, honest dialogue, and a commitment to healing the wounds of the past. It’s not an easy process, but peace must take root.

The role of education in peacebuilding

Education plays a vital role in building peace. It helps people understand each other better, and it encourages us to solve problems with empathy and knowledge instead of violence. For me, education was the key to transforming my thoughts from revenge to healing. I strongly believe that if more young people have access to education, we could reduce violence and create a more peaceful world.

In short, being a refugee has taught me many lessons. Conflict can take away everything you have—your home, your family, and your sense of identity. But it can also teach you valuable lessons about resilience, forgiveness, and the power of hope. Now, I believe that peace is possible, even in the most difficult situations.

We all have a role to play in promoting peace. By working for justice, understanding each other, and committing to reconciliation, we can build a world where people no longer have to live in fear or face the pain of being displaced. I hope my story encourages others to seek healing instead of revenge and to believe in the possibility of peace, no matter how tough the journey may be.

With hope and solidarity,

Armand Dushime